A year ago I wrote an article describing my first experiences scaling Meteor. In short, I created a popular fantasy football website using Meteor. At a certain point, my service started slowing down. The single server I had running the game could no longer handle the load. I was able to solve these early scaling issues by — among other things — adding additional servers.

Well, when last summer’s new season of football arrived, I once again ran into scaling issues. Adding more servers alone wouldn’t solve these problems. But I did manage to overcome them.

This article will explain things I learned this time around, broken down into six pieces of practical advice.

One thing that has changed since my last article is that the Meteor Development Group has finally released Galaxy, which gives you Meteor hosting at $29 per container per month. This doesn’t include database hosting, but you can use something like Compose or mLab for that. Alternatively, you can self-host the database on AWS or DigitalOcean. This will be cheaper, but will require more work on your part.

I myself use DigitalOcean for hosting. The site runs on $5/month, 512MB droplets with one Meteor instance running per droplet. I use Meteor Up(Mup) for deployment and Compose.io for database hosting.

Whether to go with DigitalOcean or Galaxy is up to you. Galaxy will do a bunch of stuff for you and will save you time. Going the DigitalOcean route will save you $24 per container per month. For a lot of companies going with Galaxy makes the most sense since developer salaries will be far more expensive. In any case, I’ll leave the business decisions up to you.

Moving on. There are a few things that really helped scale our Meteor app this summer. We had some bad days. It really wasn’t smooth sailing at times, but we got through it.

A summary of lessons learned

Here are the major lessons I learned from my year of scaling:

Lesson #1: MongoDB indexes are super important!

Lesson #2: Having too many Meteor instances is a problem!

Lesson #3: Don’t worry about scaling Nginx.

Lesson #4: Disconnect users when they’ve been away for a while

Lesson #5: Will Griggs is on fire

Lesson #6: Take a cue from how they scaled Pokemon Go

Let’s go through these one by one.

Lesson #1: MongoDB indexes are super important!

So this one was an amateur mistake. Every article on scaling Meteor tells you to use indexes. And I did! But one index was missing, and I got burned for it — really burned — on the most important night of the year for us.

Explaining indexes by way of example. If you have 10,000 player scores and want to find the highest score, in a regular case Mongo would have to go through all these scores to find the highest one. If you have an index on the score, then Mongo saves a copy of all the scores in either ascending or descending order, and will find the highest score in a fraction of the time. You can read more about indexes on the MongoDB website.

In a Meteor project, I recommend having one publications.js file that contains all your publications. Below each publication you should have code that creates the necessary index for each publication. The code to create an index in Meteor looks something this:

Meteor.startup(function () {

Teams._ensureIndex({userId: 1, _id: 1});

});

The _id field has an index by default so you don’t need to worry about that.

Getting into the details. I use Compose.io for MongoDB hosting. They’ve been fine, and support has also been okay, but don’t listen to them when they think all your problems can be solved by adding more RAM. This isn’t true. It might work sometimes, but in my case it was just nonsense advice.

I use Kadira.io for performance monitoring. Every Meteor app should use Kadira and the basic package is great and free, so no reason not to. (Update: Kadira is currently still an obvious choice for Meteor apps, but the team behind Kadira recently moved away from Meteor, so beware of that for the future.)

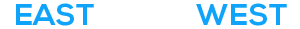

In Kadira I was seeing graphs such as these:

At a certain point the PubSub and Methods Response time become ridiculously large. Anything above 1,000 ms to respond is problematic. Even a 500ms response time can be bad. But 10–20 seconds as an average response time for an hour straight basically means your users hate you and your app is barely working for them.

In general, when things are performing slowly, I just add more servers. And I did that here too, except this time, adding more servers just made things worse. Far, far worse. But we’ll get to that later.

So at this point, what you do is you scramble around Google and spam StackOverflow and the Meteor forums.

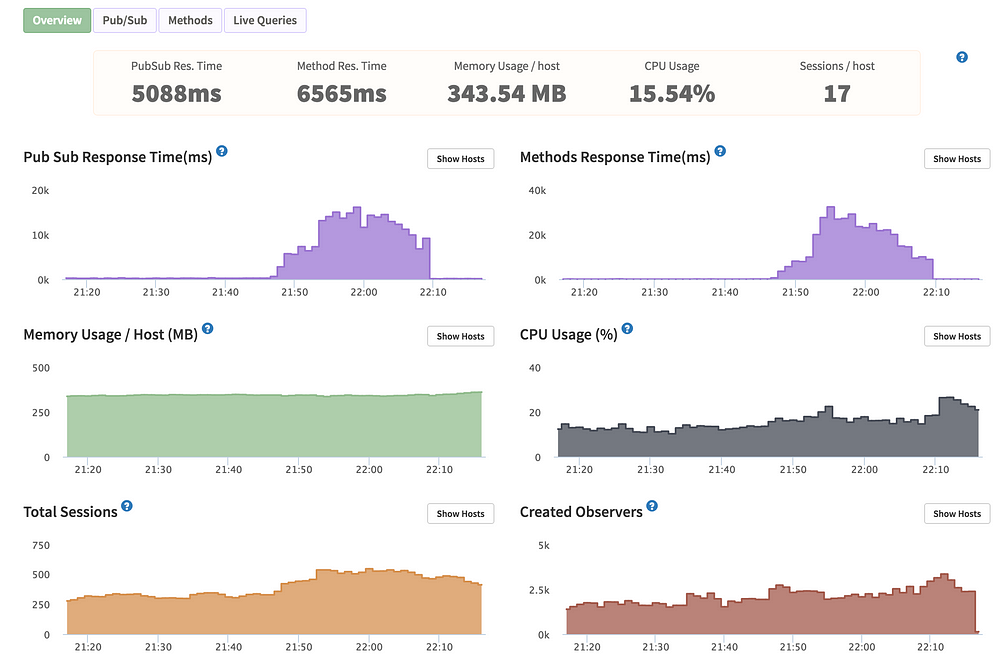

Eventually I landed upon this gem in the Kadira dashboards:

From this we see that the database is taking forever to respond. Adding more Meteor instances is not going to help us here. We need to sort out Mongo.

Kadira was no good at showing me why the database was responding so slowly. Every publication and method was showing a very high database response time.

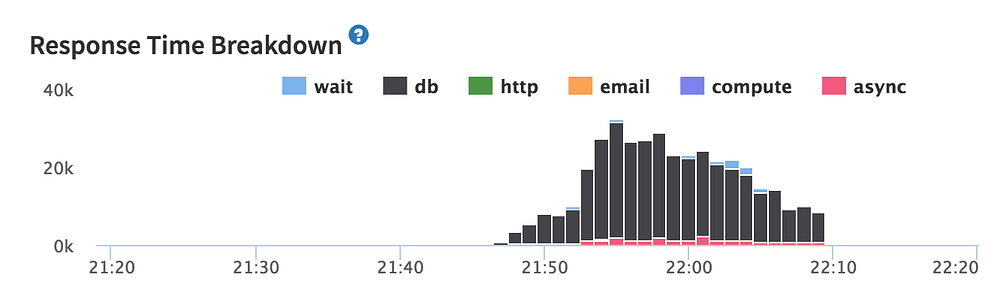

The answer came from visiting Compose.io at peak times. On the dashboard, you can have a look at the current ops (current operations) that are running at any given moment. I saw something like this (but far worse):

I had no idea what all this mumbo jumbo was, but you’ll see that each op has a secs_running field. In the image above it says 0 seconds for everything, which is great! But what I was seeing during peak time was 14 seconds, 9 seconds, 10 seconds… for the different operations that were going on! And it was all coming from the same query being made by my app.

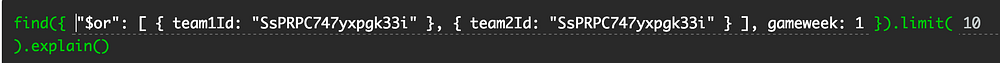

I ran this query myself and it really did take something like 16 seconds to get a response! Not good! And running it with explain (as some on the Meteor forums suggested) showed that 180,000+ documents were being scanned! Here is one of the problematic queries:

Anyway… lo and behold, there’s no index set up for this query. I added the following indexes:

Meteor.startup(function () {

HeadToHeadMatches._ensureIndex({ team1Id: 1, gameweek: 1 });

HeadToHeadMatches._ensureIndex({ team2Id: 1, gameweek: 1 });

});

After this the whole database starts acting quickly again. This one problematic query was slowing down the entire database!

UPDATE: based on Josh Owen’s comment, a better way to do add indexes is to use Collection.rawCollection and createIndex, but the above code will work for you till at least Meteor 1.4.2.

Lesson #2: Having too many Meteor instances is a problem!

So once you learn how to scale to multiple instances, you hope it’s the end of all the scaling misery. Alas, this is not the case. And adding too many servers will hurt performance at a certain point.

This is because Mongo uses additional RAM for each connection to the database. I must have had around 60–70 instances connected to my database at some point, and Mongo did not like it, nor did I need that many. The Meteor instances weren’t the bottleneck for performance.

You can give Mongo more RAM of course, but just be wary of what happens when you keep adding more servers. You might be taking the load off of each Meteor instance, but you’re adding load to Mongo creating a new bottleneck.

Lesson #3: Don’t worry about scaling Nginx

One thing I was worried about this summer was that Nginx would be my bottleneck. This will rarely be the case. Nginx should be able to handle thousands of concurrent users without a problem.

I did speak to a company that was having troubles with Nginx a few months ago. They had to handle a couple of thousand concurrent connections. You can read this article for some more tips about optimising Nginx for high traffic loads.

Some highlights from the article that are worth using immediately:

Turn off access logs:

By default nginx will write every request to a file on disk for logging purposes, you can use this for statistics, security checks and such, however it comes at the cost of IO usage. If you don’t use access logs for anything you can simply just turn it off and avoid the disk writes.

Worker processes and connections:

Worker Processes

The worker process is the backbone of nginx, once the master has bound to to the required IP/ports it will spawn workers as the specified user and they’ll then handle all the work. Workers are not multi-threaded so they do not spread the per-connection across CPU cores. Thus it makes sense for us to run multiple workers, usually 1 worker per CPU core. For most work loads anything above 2–4 workers is overkill as nginx will hit other bottlenecks before the CPU becomes an issue and usually you’ll just have idle processes. If your nginx instances are CPU bound after 4 workers then hopefully you don’t need me to tell you.

An argument for more worker processes can be made when you’re dealing with situations where you have a lot of blocking disk IO. You will need to test your specific setup to check the waiting time on static files, and if it’s big then try to increase worker processes.

Worker Connections

Worker connections effectively limits how many connections each worker can maintain at a time. This directive is most likely designed to prevent run-away processes and in case your OS is configured to allow more than your hardware can handle. As nginx developer Valentine points out on the nginx mailing listnginx can close keep-alive connections if it hits the limit so we don’t have to worry about our keep-alive value here. Instead we’re concerned with the amount of currently active connections that nginx is handling. The formula for maximum number of connections we can handle then becomes:

worker_processes * worker_connections * (K / average $request_time)

Where K is the amount of currently active connections. Additionally, for the value K, we also have to consider reverse proxying which will open up an additional connection to your backend.

In the default configuration file the worker_connections directive is set to 1024, if we consider that browsers normally open up 2 connections for pipe lining site assets then that leaves us with a maximum of 512 users handled simultaneously. With proxying this is even lower, though, your backend hopefully responds fairly quickly to free to the connection.

All things considered about worker connections it should be fairly clear that if you grow in traffic you’ll want to eventually increase the amount of connections each worker can do. 2048 should do for most people but honestly, if you have this kind of traffic you should not have any doubt how high you need this number to be.

Lesson #4: Disconnect idle users

This one is important! I don’t why this isn’t a bigger thing in the Meteor community!

Disconnect users when they’ve just left their tab open. It’s so simple to do and saves precious resources.

To disconnect automatically you can use this package: mixmax:smart-disconnect.

Lesson #5: Will Griggs is on fire

If you got this far in the post, you’re probably feeling super inspired and in the mood for a football chant. I present you with Will Griggs:

There wasn’t actually a point here. It just seemed like the appropriate thing to write at this point in the article. But if we actually want to learn a lesson from it then here goes:

If you’re a solo developer, and you have thousands of people relying on your app to work right now, things can get stressful. My advice to you (and to myself): calm the heck down. Listen to some Will Griggs on Fire. Hopefully you’ll work it out, and even if things mess up, it’s probably not as bad as you think.

Pokemon Go was pretty awful at the start. Servers were constantly overloaded, but people kept coming back to play. From a business perspective, Niantic still made a killing. The hype has now died down, but that has nothing to do with their scaling issues, or the many early bugs. It’s just the end of the fad.

So the life lesson, listen to Will Griggs when you’re stressed out.

Lesson #6: Take a cue from how they scaled Pokemon Go

On the topic of Pokemon Go, lets talk a bit about what happened. Firstly, Pokemon Go will not happen to you. Pokemon Go had a strong team of ex-Googlers that knew how to do deal with enormous loads, but even they got caught out with the popularity of the app. They were ready for a big load, but not or a load the size of Twitter.

Some apps around Pokemon Go also popped up. Pokemon Go chat apps, and Pokemon Go Instagrams started popping up and became very popular, very quickly with a million users in a matter of days. Some of these apps were developed by solo developers and handling the load was a challenge for them.

There’s this article about how someone built a Pokemon Go Instagram app with 500,000 users in 5 days and ran it on a $100 per month server. That’s impressive. And the takeaway from the article is that you can build a quick MVP that scales if you know what you’re doing.

If you can do that, that’s definitely great, but if you’re a young and inexperienced developer that may not be possible. I would recommend to go and build your dream app and not worry too much about what happens when you need to scale.

If you can build things the right way from the get go that’s definitely a plus and it’s definitely worth asking more experienced developers for advice to try and get things right from the start. But don’t let the fear of scaling hold you back from creating your dream app. The harsh reality is that people probably won’t like your app and it would be impressive if you can get 100 people to use it.

But following the principles of the lean startup, it’s better to build something, get it into the hands of real users, and get feedback, than to never launch due to fear of not being able to deal with a heavy load.

Looking Ahead

These episodes dealing with scaling have been a burden and ideally I would have preferred not to have to deal with these issues. It would be great if things just worked and you could push off scaling issues as long as possible. Because of this I’ve started looking at other platforms that handle scale better.

One such platform is Elixir which is built on Erlang. Erlang is what Whatsapp uses and allowed a team of 35 engineers to scale to 450 million users! Even today, with close to 1 billion users, Whatsapp has a team of only 50 engineers! That’s pretty incredible and you can read more here. How did they achieve such awesome scale for a real time app with so few people? The answer is Erlang. And today you can utilize the power of Erlang with Phoenix Framework and Elixir. We’re still using Meteor, but some aspects of the app I am considering moving over to Elixir which will enable us to hit large scale live updates.

I’d also take a look at Apollo which will work with Meteor or any Node.js server. Apollo will help you scale Meteor, because you don’t need every single publication to be reactive when using Apollo (which are the biggest drain on server CPU for Meteor apps.) You can achieve a similar result using Meteor methods to send data instead of publications.

One last point is that despite many influential Meteor developers recently leaving the community, there have been some developments on the scaling front with regards to scaling. Check out the redis-oplog package and discussion for more. It’s a very new package and I’d still say it’s in beta from my little experience playing with it a week ago.